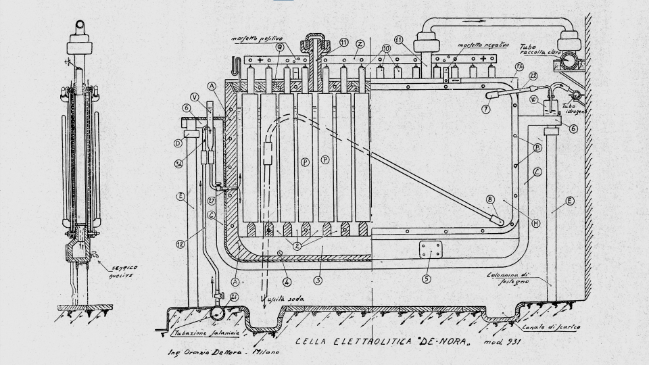

Oronzio De Nora, after graduating in engineering, decided to enroll in the electrochemistry graduate course and, together with Professor Giacomo Carrara, worked on the electrolysis of alkali chlorides. Oronzio De Nora obtained the first patent of his career as a researcher and industrialist. Sodium hypochlorite, a product widely used in the textile industry for bleaching fabrics and a fixative in photographic printing processes, is produced using sodium chloride electrolytic cells in which bipolar electrodes are mounted and arranged vertically and horizontally. Seeking to make the production process more efficient, Oronzio De Nora noted that an inclined position of the electrodes would have provided many advantages. Indeed, the system produced dense caustic soda in the lower cathodic part and chlorine, in the gaseous state, in the upper anodic part. The inclination of the electrodes would have allowed the heavier former to slide downward and react with the lighter latter, which would spontaneously rise upward. The meeting of the two substances would then have formed hypochlorite.